Why the England and Wales Cricket Board is taking inspiration from UFC and behaving like a ‘digital agency’

The quintessential English game is learning lessons from US sports and taking a forward-thinking approach to digital and content marketing to convince a new generation of fans and sponsors to look at cricket in a different way.

It may come as a surprise to hear that the man responsible for marketing English cricket takes inspiration for that task from the Ultimate Fighting Championship – but then there’s much about this ever-modernising sport that defies its stuffy stereotype.

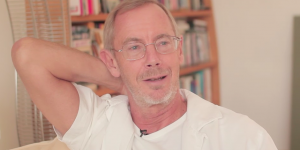

The England and Wales Cricket Board’s commercial director, Sanjay Patel, is increasingly looking beyond the game’s traditional boundaries to find the next generation of players, supporters and sponsors it needs to “futureproof” itself. “If we’re just thinking now it’s a contest between cricket, rugby and football, we’ve got it wrong,” he says.

In his three years with the ECB, Patel has spearheaded a dramatic digital transformation drive that has seen the governing body wise up to the commercial value of its star players and digital broadcast rights and put those assets at the heart of its sponsorship packages with brands such as Natwest, New Balance and Royal London. In the most striking and surprising demonstration of its commitment to this approach, the ECB has opened its own in-house content studio, which is currently making branded videos for Toyota.

“That’s us starting to almost behave like a digital agency as opposed to a governing body that does digital within it,” says Patel. “It’s a USP for us because I don’t think any other sport is actually doing that.”

The ECB is broadening its digital horizons partly to solve a problem of its own making. Since the peak of the sport’s modern-day popularity in England – the 2005 Ashes victory broadcast on Channel 4, which made household names of Andrew Flintoff, Kevin Pietersen and Michael Vaughan – there has been no live cricket on British terrestrial television. An exclusive broadcast deal with Sky, which is reported to be worth £280m and runs until 2019, proved too lucrative for the ECB to resist but has been criticised by ex-players such as Vic Marks for stunting the game’s growth. Statistics released last year showed that only 278,600 people in the UK regularly played cricket – almost half of what it was 20 years ago.

There have been rumours that live cricket could return to free-to-air television when the Sky deal ends, but Patel plays such suggestions with a straight bat, preferring instead to praise Sky’s output. “Sky does a great job for us in terms of the amount of cricket it covers, and the way it produces it is second to none and wins a lot of awards,” he says. But the establishment of the nine-strong digital and four-strong content teams is evidence of the sport’s desire – and need – to reach a much a wider audience.

The digital activity, therefore, is intended to take the exploits of captain Joe Root to audiences who may never have seen him score any of his 4594 test match runs live. “The area we can play best in is helping to create a narrative for our competitions on digital and social,” says Patel. “The access that we’ve got to players and to content means we can create magazine-style programmes and short-form clips. Our focus, particularly in the next two to three years, is around creating that narrative around the live.”

It is in this approach that Patel has been motivated by the likes of UFC, the NFL and even the recent Anthony Joshua-Wladimir Klitschko fight. “When you have a UFC night, the amount of content they create before that is phenomenal and I think sport can take huge learnings about how they do that,” he says. The Joshua heavyweight contest was a “case study” in how to hype a fight without resorting to trash-talking, according to Patel. “I like the way they’ve respected their sport but they’ve also managed to create huge narrative around that fight, which captured the imagination of the nation.”

‘Respecting the sport’ is one of the most important considerations for the man charged with promoting a game so traditional that kit supplier New Balance’s decision to reinstate the England team’s cream cable knit sweaters made headline news. But while the leisurely pace of five-day test match cricket may not be everyone’s idea of a thrill ride, the more visceral shorter format of the game, Twenty20, represents huge potential for growth. “We know from our analysis that when England play T20, both men’s and women’s, the interest, the viewership and the following peaks,” Patel says. “It’s clearly the format that reaches the widest audience.”

T20 boasts hyped-up crowds under floodlights and kamikaze batsmen in day-glo kits trying to slog the ball into oblivion at every opportunity. In presentational terms, its boisterousness bears more resemblance to a night at the darts than cricket’s classic image of genteel play in all white kits interrupted only by afternoon tea or a downpour. As such, T20’s razzmatazz isn’t always to the purists’ tastes, but Patel believes it is possible to satisfy the traditionalists’ desire for cricket to preserve its esoteric principles while also modernising the sport to appeal to younger audiences.

“The traditionalists that we talk to want the game to progress, they don’t want the game to stand still,” he says. “They love the game and they want it to grow, and they understand that one of the ways of growing the game is to promote the shorter format.

“Now what they will say to us is ‘please leave test cricket, and please leave the longer format of the game, and don’t mess too much with that, because that’s what we love’. One of the great things about cricket is it’s got a portfolio of formats and so you can segment your audience and appeal to different parts of that audience.”

Because it sees T20 as the most obvious way to attract new fans, the ECB recently unveiled plans to launch a regional T20 tournament across the country in 2020. Patel has big ambitions for the competition, which is modelled on Australia’s glitzy Big Bash League, and has enlisted Futurebrand to create the tournament’s identity having been impressed by the agency’s work on the London 2012 Olympic and Paralympic Games.

The Times has speculated that the ECB will spend as much as £6m a year marketing and running the tournament, but Patel disputes that number. “I don’t know where they get their figures – £6m would be great,” he laughs. “What we will definitely do is spend the right amount of money on it. We’ll go and do the proper analysis behind that. How much do we need to spend to make sure this is the highest awareness sports tournament between June and August?”

There is said to be an appetite within the ECB for at least some of the T20 matches to be shown on terrestrial television. With the broadcast deals still to be concluded, Patel is coy about who will emerge victorious, but the Guardian reports that the BBC, ITV, Channel 4, Channel 5, Sky, BT Sport, Eurosport and – intriguingly – Twitter and Facebook have each been involved in talks. “We understand that the media landscape is going to change rapidly over the next three years, so by the time that we get to launching this tournament we’ve got to ensure that this competition hits the right audience, a family audience,” Patel says.

Patel’s long-term strategy goes like this: get families and youngsters interested in the short-form game, with its high-octane style, and “as people get more involved in the game, and as they grow their affinity levels and understanding of the game, they will then migrate to the longer format”. To do that, the ECB has to make sure that it can lure them to T20 first. “The way we’re thinking about it is, how do we launch a global entertainment brand in 2020?” Patel says.

This is cricket – but not as we know it.

This article is about:

Get the Newsletter

Get the Newsletter

Keep up to date with the latest news and insights.

The Drum Marketing Awards have been running for over a decade, rewarding the best in UK marketing. One of The Drum's biggest awards, they celebrate everything from global marketing strategies, branded...

Find out more